The recent removal of the common plastic straw from venues is well intentioned and falls within a greater logic that as consumers and individuals, we must be cognizant of our own contribution to global pollution and the rising tide of climate change. And for many, this transition away from single-use plastic products is easy. However, for people with disabilities, the seemingly arbitrary removal of a straw makes life a lot more difficult. Widely accessible plastic straws are an important tool in the day to day life of people with disabilities. Straws are helpful for those who cannot lift the weight of a full cup, can act as a conduit for people who have difficulty craning their neck over a drink, and can help when one needs to swallow their medication with liquid. Straws, in the case of people with a disability, are not a luxury, they are a necessity. Eco-friendly straws melt in hot liquids, and metal straws can be dangerous for people who may have biting issues. Additionally, the discussion surrounding the removal of plastic straws not only lacks a consideration for people with disabilities, but also a connection and focus from a greater, far more potent contributor to climate change and pollution—companies.

Vertigo

Your Straw Is Not The Only Reason Turtles Are Dying.

By Alyssa Rodrigo

Pubs, restaurants, and your local burger joint alike are going through a break-up. The beloved plastic straw, in all its multicoloured and bendy convenience, is on its way out. Its rebound? Paper and biodegradable straws, and, if you’re lucky, those sexy metal ones that hurt your teeth. It’s true, plastic straws are bad for the environment, and they’re especially bad for unsuspecting turtles and birds. But, they’re also far from our only concern.

Even if every single person on earth ceased to use plastic straws, transitioned to canvas shopping bags, and carried around re-usable water bottles, the onslaught of global warming and the mass extinction of marine species would remain inexorable.

According to the findings of two Australian scientists, even if all the plastic straws in the world drifted into our oceans, it would still only account for 0.003% of 8 million metric tonnes of plastic estimated to enter the water this year. While our focus veers to single-use plastic consumption, our attention is diverted away from fishing companies, for example, who are responsible for 640,000 tonnes of discarded plastic fishing nets in the ocean each year. Because of this, over 100,000 whales, dolphins, and other marine life become entangled in nets each year. According to a report by World Animal Protection, abandoned nets have been found to kill marine life up to four times more than all plastic debris in the ocean combined. The narrative that the atomized actions of the individual is enough to substantiate change in a dying planet is deeply flawed.

As was revealed in an investigation by InsideClimate News in 2015, the multinational gas and oil giant ExxonMobil knew about climate change and its effects as far back as the 70s. Instead of using this vital information to quell the predicted rise in sea levels and the devastating impact of carbon pollution, the company invested $30 million in think tanks to systematically spread doubt about climate science. In 1978, one of ExxonMobil’s senior scientists, James Black told an audience of board members that “the most likely manner in which mankind is influencing the global climate is through carbon dioxide release from the burning of fossil fuels.” He wrote, again in 1978, “that man has a time window of five to ten years before the need for hard decisions regarding changes in energy strategies might become critical.”

The decision of one company and their greed for profit has meant that the world has lost crucial decades which could have been spent diverting economies to a more sustainable future. Had this information been utilised, the Great Barrier Reef might have continued to flourish, permafrost in Siberia might have remained unthawed, and future generations might have had the opportunity to live in a world bereft of toxic carbon pollution.

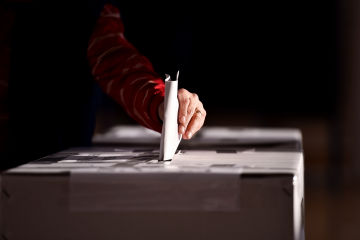

And yet, here we are, 40 years after Black’s discovery, hoping that removing straws, plastic bags, and water bottles from our daily consumption will be enough to save our planet. And still, Turnbull and his coalition have their eyes set on the Adani coal mine, with Bill Shorten sitting comfortably on the fence.

It is easy, as individuals, to turn inwards and reflect on our own behaviours and how we might contribute to a more sustainable planet. And whilst individual action is important, it has to be linked to a greater, collective effort to hold companies and governments accountable for their indifference and inaction towards climate change.